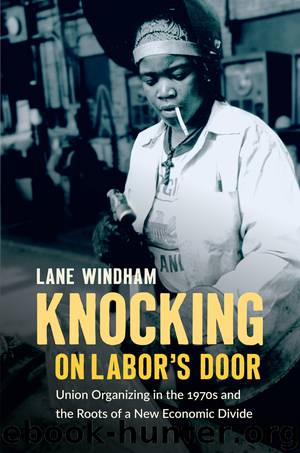

Knocking on Labor's Door by Lane Windham

Author:Lane Windham

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

Women’s Rights Comes to the Office

It was no coincidence that some of the most forward-thinking labor organizing in the 1970s grew up among clerical workers. This group was primarily composed of women who found themselves at the epicenter of two major shifts: the mass entry of women into America’s workforce and the cultural transformations rooted in the women’s movement. By 1979 women made up a full 42 percent of all workers, up from 30 percent in 1960, and women were more likely to earn their paycheck in clerical work than in any other job. One in three women who worked for wages did so as an office worker.4 Meanwhile, secretarial work was undergoing a major shift of its own as technologies like photocopiers, memory typewriters, and, increasingly, computers furthered a century-long process of mechanizing office work.

Women ran the new office machines, and they did it cheaply. Early twentieth-century employers had learned that they could keep costs down by employing women as typists and stenographers, displacing the young aspiring businessmen who had once served as clerks. By the 1970s, a full 97 percent of typists were women. Yet female clericals earned less than men who worked as operatives, salesmen, or service workers—in fact, they earned less than all men except farm workers. “I replaced a man who was making $140 a week at $80,” wrote one shipping clerk at A&P Tea Company in a 9to5 survey. “At my present raise rate, it will be eight years by the time I reach that pay.”5

The office workers who organized wanted to upend unfair, gender-typed treatment in the office as much as they sought to address low pay, and the new ideologies of the women’s movement gave their efforts momentum. The expectations that women clericals would get the coffee, buy the presents, and pamper their bosses collided with a growing sense of professionalism and entitlement. “My greatest gripe, besides the obvious problems of low pay and lack of respect, is that the men with whom we work refuse to recognize us as mature, adult women.… I am not a ‘puss,’ or a ‘chick,’ a ‘broad’ or a ‘dear.’ I am a WOMAN and I have a name, a full name of my own,” insisted one Boston office worker, writing in response to an early 9to5 newsletter in 1973.6

Some 9to5ers embraced the new ideas of women’s equality, even if they chose not to embrace its language. Judith McCollough, an office worker at Travelers Insurance in Boston, was typical of such working-class women attracted to the group. “I’d been interested in the women’s movement,” but was “slightly intimidated by it,” remembered McCollough. Though she “identified with the idea that women should … do all the things that they wanted to do … The National Organization for Women … just didn’t seem to connect to me.” McCollough went on to join 9to5’s staff and later became a national union organizer.7

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Brazilian Economy since the Great Financial Crisis of 20072008 by Philip Arestis Carolina Troncoso Baltar & Daniela Magalhães Prates(138670)

International Integration of the Brazilian Economy by Elias C. Grivoyannis(111057)

The Art of Coaching by Elena Aguilar(53249)

Flexible Working by Dale Gemma;(23292)

How to Stop Living Paycheck to Paycheck by Avery Breyer(19727)

The Acquirer's Multiple: How the Billionaire Contrarians of Deep Value Beat the Market by Tobias Carlisle(12326)

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Kahneman Daniel(12301)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12026)

The Art of Thinking Clearly by Rolf Dobelli(10487)

Hit Refresh by Satya Nadella(9132)

The Compound Effect by Darren Hardy(8964)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8393)

Atomic Habits: Tiny Changes, Remarkable Results by James Clear(8342)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(8047)

A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas(7843)

Change Your Questions, Change Your Life by Marilee Adams(7780)

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(7706)

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(7486)

Win Bigly by Scott Adams(7194)